The Great Mosque of Cordoba

In the southern half of Spain, in one of the oldest cities in the region, lies one of the most unique structures in religious history. Beginning in 152 BC, in a city that would become the capital of the Islamic Emirate and, for a time, the most populous city in the world, a sacred edifice was erected that has fascinated the public for generations. First, it was a temple built by the Romans, next it was converted to a Catholic church by the Visigoths and then it became an Islamic mosque built by Abd al-Rahman I in 784 AD before being altered in a way that has never been done before or since. The Great Mosque of Cordoba is a monument to the religious changes that have taken place in Spain since the area was first populated.

In the 206 BC, Rome conquered the Carthaginian inhabitants of the area now known as Spain. For centuries Rome ruled the area that they named Hispania Ulterior Baetica, of which Cordoba was the capital. During that time, around 169 BC, Roman consul Marcus Claudius Marcellus built a temple to their god, Janus. In 572 AD, Catholic Visigoths conquered Cordoba and began converting the Temple of Janus into a Christian church that they dedicated to St. Vincent. A few short years later, around 710 AD, Muslim forces overran Cordoba and seized control of the city. For a time, Christians and Muslims shared the Church of St. Vincent, with areas set apart where Christians and Muslims could worship separately.

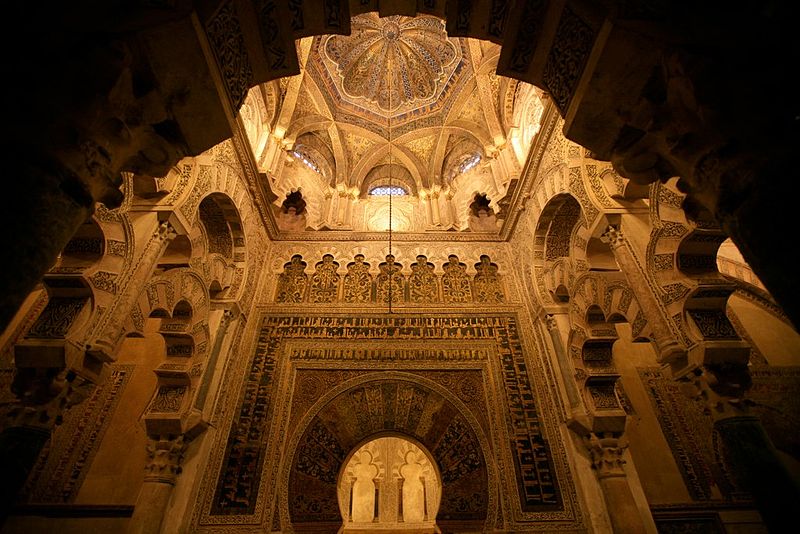

Cordoba Mihrab – Courtesy of Khan Academy

Cordoba Mihrab – Courtesy of Khan Academy

But then, in 766 AD, Cordoba became the capital of the newly-designated Muslim region of al-Andalus under the rule of Abd al-Rahman I. By order of Abd al-Rahman I, who purchased the Christian half of the Church of St. Vincent from the local congregation, the Church of St. Vincent was destroyed and a grand mosque put in its place. Over the next two decades, with the intent to recreate his birth city of Damascus, al-Rahman worked to design a mosque that would rival the Great Mosque of Damascus while incorporating local styles and elements. This mosque was begun in 784 AD and over the course of the next two hundred years, would receive various modifications and alterations by the Muslim rulers of al-Andalus. By the time the Great Mosque of Cordoba was finally completed over 200 years later, it had become the most innovative Islamic Mosque in the world.

The original Great Mosque of Cordoba was architecturally innovative for a number of reasons, though it did have features and characteristics that were common to that era. It is the use of those common features and characteristics that made this structure the fascinating marvel that it is. To examine fully whether or not the Great Mosque of Cordoba was truly an innovative masterpiece, let us compare it to the other prominent Islamic structure of that time: The Great Mosque of Damascus, also known as the Umayyad Mosque. The Umayyad Mosque was completed in 715 AD, a full 69 years before the Great Mosque of Cordoba was even begun, and was the most prominent Islamic building of the time, serving as one of the main architectural inspirations for the Great Mosque of Cordoba. Along with sharing architectural elements and themes, the Great Mosque of Cordoba also follows the tradition of Umayyad Mosque in being built over the site of a local Christian church. Aside from that feature, these two magnificent structures have various other similarities as well as several distinct differences.

Examining the exteriors of each structure, you will immediately see some architectural differences. Whereas the Umayyad Mosque uses arches mainly as a structural element, the Great Mosque of Cordoba uses arches as both structural and decorative elements. The Umayyad Mosque uses two sizes of a standard, simple, repeating arch while the Great Mosque of Cordoba uses a variety of styles, sizes and designs. There are poly-lobed arches, horseshoe arches and interlacing horseshoe arches. An interesting fact to note about the interlacing arches is that Islamic artists “[drew] from Christian traditions [and] a variety of traditions in creating their art [and] they also….mimic what we see in Christian art of the Romanesque period where we see a lot of interlacing arches and that’s very unusual” (Ross).

Another key difference of the exterior is that Umayyad Mosque has three minarets while the Great Mosque of Cordoba only has one, though it does not appear like one anymore and we will go into the reason for that later. Exterior similarities between the two mosques include the elaborately decorative doors with artistic elements around the doors, though the specific artistic styles differ; Umayyad Mosque utilizes stained glass while the Great Mosque of Cordoba displays intricately designed mosaics.

Moving on to the interior, we see one of the more distinct elements of the Great Mosque of Cordoba. Inside the mosque, there are 856 columns supporting a series of two-tiered arches that support the roof. This is called a Hypostyle hall. While the use of arches and columns was not unusual during and prior to the early-Christian era, the way the arches and columns were used in the Great Mosque of Cordoba was. Columns had been used for centuries in buildings such as the Parthenon and many early Christian basilica-styles church, but what makes the columns in the Great Mosque of Cordoba so special is that the number of them, 856, is “the most columns in any single building ever” (Ross). As for the style of the arches attached to those columns, that, too, is unique.

Bi-level arches had been used prior to the Great Mosque of Cordoba in Islamic, Christian and Roman structures such as the aqueduct bridges of Segovia and Pont du Gard, the Verona Arena, the Colosseum, the Great Mosque of Damascus, Dome of the Rock, the Basilica of San Vitale and Hagia Sophia. The difference, however, is that the Great Mosque of Cordoba did not separate the tiers with straight levels of brick or concrete. These other structures had a distinct separation of arches because the second or third sets of arches were usually on a second or third floor of the building. The Great Mosque of Cordoba did away with the common practice of putting tiered arches on separate and distinct levels by removing the separating plane from the structure and instead, extended the arch column up to support a second, freestanding arch. This created an innovative design that had never been seen before.

Aside from putting a twist on the traditional style of bi-level arches, the Great Mosque of Cordoba utilized a wide variety of arch designs and placement. The placement of multiple rows of arches in the layout of a church was something that was very common. What wasn’t common was using a variety of designs for those arches. Inside the Great Mosque of Cordoba are further examples of interlacing arches, poly-lobed arches, horseshoe arches, interlacing horseshoe arches and the standard single arch. Most of the arches have an alternating stone and red brick pattern while others are covered in mosaics.

The ideas for these different designs and their decoration came from Visigothic, Byzantine, Christian and Islamic styles. The horseshoe arch is a Visigothic feature, the interlacing horseshoe arch is a Christian feature and the alternating stone and red brick comes from the Byzantine tradition. This practice of adapting and incorporating previous architectural styles and local elements is what makes Islamic architecture so one-of-a-kind. “Islamic architecture is unique in the non-Western world in that it alone – not Buddhist, not Hindu, not Pre-Columbian – shares many of the forms and structural concerns of Byzantine, Medieval, and Renaissance architecture, having grown from identical roots in the ancient world” (Trachtenberg, 215).

Moving on through the interior we see further similarities between the two mosques. Both have enclosed courtyards, rectangular prayer halls and repeating abstract patterns adorning the walls. Islamic artists believe that by covering a space in patterns, it makes that space more holy and the reason these patterns are abstract is because Islam forbids the depiction of things observable in nature, so Islamic artists decorate their mosques in repeating floral motifs and other patterns inspired by what they see in nature. Almost every surface in both mosques is covered in some form of patterned decoration to create a luxurious and holy space. The Great Mosque of Cordoba displays these patterns by way of mosaic, which was “the most lavish way to decorate” at that time (Ross). This, though, is the last feature which the Great Mosque of Cordoba and Umayyad Mosque have in common.

The last interior feature of the Great Mosque of Cordoba is probably the most unique, and shocking, of all. While the original features of the mosque are enough to make this building an innovative piece of architecture, it wasn’t until after King Ferdinand III of Castile conquered the city in June 1236 that the most truly unique feature of this ancient masterpiece came to be. Desiring the magnificent edifice for their new place of worship, the local bishop ritualistically cleansed the building and declared it a Catholic cathedral. Soon after, various sections of the mosque were converted into chapels. Over the next 600 years, many other changes would be made to the mosque to bring it more in line with Christian churches, but the biggest change of all happened almost immediately.

In 1252, Alfonso X succeeded King Ferdinand III and received permission from the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V to make the most extreme change of all: the insertion a full-sized Renaissance-style Catholic cathedral into the center of The Great Mosque of Cordoba, the removal of all but one minaret, and that one was converted into a bell tower. While this cathedral is striking and masterful, its inclusion caused incredible shock and dismay. Upon seeing the completed structure for himself, Emperor Charles V is said to have declared, “they have taken something unique in all the world and destroyed it to build something you can find in any city” (Wikipedia).

|

|

|

As you can see, the Great Mosque of Cordoba is an architectural marvel that is both innovative and typical. It includes several elements of architecture and style that were typical of the period when it was created, but it also has several elements that were innovative and unique. But these elements are not all that make this work an important part of art history. The elements that make this structure so important vary. One reason is that the Great Mosque of Cordoba was built about 175 years after Islam began, making it one of the first mosques ever built. Another reason why this structure is so important is because it includes the deliberate incorporation of so many local, Visigothic and Christian architectural traditions that would later become very influential in the building of future Islamic buildings. The final two reasons why this structure is so important are that it is the only mosque on earth with a cathedral inside and that it includes such a unique Hypostyle hall. The extensive use of arches and columns makes the gallery look much larger than it is and gives the illusion that it goes on for forever.

The Great Mosque of Cordoba is such a fascinating and timeless piece of ancient history. Even now, it still holds an important place in the hearts of many. Fought over for centuries by Christians and Muslims alike, the Great Mosque of Cordoba will forever be a place that stands for the harmony of artistic, architectural and religious traditions.

Works Cited

“The Art of the Umayyad Period in Spain (711-1031).” Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, n.d. Web. 13 Nov. 2014. <http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/sumay/hd_sumay.htm>.

“Córdoba, Andalusia.” Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, 11 Dec. 2013. Web. 13 Nov. 2014. <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Córdoba,_Andalusia>.

“Córdoba: Historical Overview.” Spain: Then and Now. Spain: Then and Now, n.d. Web. 13 Nov. 2014. <http://www.spainthenandnow.com/spanish-history/cordoba-historical-overview/default_41.aspx>.

Demirhan, Meryem. “The Great Mosque of Damascus.” Academia.edu. N.p., 26 May 2013. Web. 14 Nov. 2014. <https://www.academia.edu/3769159/The_Great_Mosque_of_Damascus>.

“Features and Characteristics.” Santa Iglesia Catedral De Córdoba. The Cathedral Cordoba, n.d. Web. 13 Nov. 2014. <http://www.catedraldecordoba.es/Elmonumento.asp?idp=7&pag=1#>.

Gates, Sandra, and Megan Smith. “Umayyad Mosque & The Great Mosque of CoÌrdoba.” YouTube. YouTube, 6 Dec. 2012. Web. 14 Nov. 2014. <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=syyFTFpJGEg>.

“Great Mosque of Cordoba, Spain.” YouTube. Ichsandzunnurraien, 13 Nov. 2011. Web. 13 Nov. 2014. .

“Historic Centre of Cordoba.” UNESCO World Heritage Centre. UNESCO World Heritage Centre, n.d. Web. 13 Nov. 2014. <http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/313>.

Labatt, Annie. “Great Mosque of Damascus.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 09 May 2012. Web. 14 Nov. 2014. <http://www.metmuseum.org/exhibitions/listings/2012/byzantium-and-islam/blog/where-in-the-world/posts/damascus>.

Mirmobiny, Shadieh. “The Great Mosque of Cordoba.” Smarthistory. Khan Academy, n.d. Web. 12 Nov. 2014. <http://smarthistory.khanacademy.org/the-great-mosque-of-cordoba-spain.html>.

“Mosque–Cathedral of Córdoba.” Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, 11 July 2014. Web. 13 Nov. 2014. <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mosque–Cathedral_of_Córdoba>.

Ross, Nancy. “Great Mosque of Cordoba.” 13 Nov. 2014. Lecture.

Trachtenberg, Marvin, and Isabelle Hyman. Architecture, from Prehistory to Post-modernism: The Western Tradition. New York: H.N. Abrams, 1986. Print.

“Umayyad Conquest of Hispania.” Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, 11 June 2014. Web. 11 Nov. 2014. <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Umayyad_conquest_of_Hispania>.

“Umayyad Mosque.” Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, 11 July 2014. Web. 13 Nov. 2014. <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Umayyad_Mosque>.

Van Der Zee, Bibi. “Córdoba: The City That Changed the World.” The Guardian. The Guardian, 02 Oct. 2009. Web. 13 Nov. 2014. <http://www.theguardian.com/spanish-tourist-board/cordoba-city-changed-world>.

Witcombe, Christopher L.C.E. “Sacred Places: Mosque of Córdoba, Spain.” Sacred Places: Mosque of Córdoba, Spain. Christopher L. C. E. Witcombe, n.d. Web. 13 Nov. 2014. .

29 Comments

Anagha Rayachoti

This was a very good read- so glad to have stumbled upon a blog that talks about history. I was in Cordoba this summer and the Great Mosque was definitely a treat!!

And interesting point about Islamic architecture using floral motifs!! I had wondered about that from long.

Erin

Thank you for reading my blog! I love writing about historical sites. This is one I had to research for my Art History class and hope to visit some day. I love all the little details at Cordoba and how unique it is.

Carmen Garnube

what is the great mosque of cordoba now?

Erin

The Great Mosque of Cordoba is currently used as a Catholic church.

Syed A.B.Siddiqui

Amazing! Stunning structural music created by Moors!

Jess

Looks awesome! Can’t wait to do some traveling in the months to come, this is so inspiring!

Anita

Thank you so much for such an informative piece. I’m a architecture fan and that mosque looks spectacular. Must be so amazing to see in person.

Regina

The architecture is stunning and rich with history.

Caitlin Cheevers

What a beautiful structure! And I’m sure it’s even more amazing in person.

xo Caitlin

Candace

Its so gorgeous! I wish we still made building like this.

becky

Thanks for letting us travel through your eyes!!!

Karissa

What an amazing place and I love the photos.

Sarah

wow. how absolutely beautiful.

Rebekah

Wow! What a spectacular building. That mosque is beautiful!

Cara (@StylishGeek)

The mosque itself is a work of art! Thank you for sharing your very informative post! 🙂

Katie Matthews

My parents took me here when I was little as we travelled throughout Spain every year during the summer. It’s truly very beautiful and a lovely place to visit too!

Katie <3

Nancy

Holy, that is one massive mosque!

Rachel @ Bakerita

Wow, this is so fascinating and so absolutely beautiful! I want to visit Cordoba so badly!

alyssa

Wow. Just, wow. What a beautiful building.

Myrabev

This is one of the funnest history lesson have had and i am not usually one to sit down and read it, the buildings look amazing the photos are just captivating

Salma

Such an interesting history and magnificent structure. I would definitely love to see it one day.

Heather

I have visited here! I didn’t see all of this because it is so huge, but what I saw was amazing! (I was young and in high school and not quite as appreciative as I would be now, so it was fun to read all about it here!)

Megan @ All That Glitters

Beautiful photos! I want to go!

Natalie

Gorgeous pictures! I’m fascinated by this region of Spain since it has so many religious and cultural influences. Love all of the history you’ve included!

Stephanie

Beautiful location and wonderful photos. I’m jealous of your travels.

Chelsea

Such incredible architecture!

Amy

My goodness, just looking at the photos of this spectacular place thrills me to pieces. I can’t imagine being able to walk through it and take pictures of it, myself. Too beautiful to be believed! And the history is quite fascinating.

Andi

Stunning! My hubby would really love to spend hours here photographing every bit!

Michelle Webber

Wow! What a spectacularly fascinating piece of architecture and amazing history! This is right up my alley. Can’t wait to read more of your blog!